Though Canada has successfully welcomed Syrian refugees, they are still at risk of developing serious life-threatening effects of PTSD and toxic stress from their experiences of conflict. A report from Save the Children has identified Syrian refugee children as having a high risk of developing toxic stress. Toxic stress is a severe form of psychological trauma that can cause life-long physical damage in the brain and other organs. The violence and circumstances Syrian children have been exposed to over the course of the conflict in Syria reflect exactly the kinds of stressors that cause PTSD and toxic stress. Save the children reported that 70% of the children they interviewed showed signs of toxic stress. Even after a victim is removed from the stressful situation, the effects of toxic stress are still present.

Long-term mental and physical effects from the trauma of the conflict in Syria can still manifest themselves-“If someone has an immediate medical need you treat it- but lifesaving is broader than that when you get past that very first response, it is about things like nutrition and education and mental health because ultimately, if those things are compromised long enough people still die.” Says Cicely McWilliam, Director of Policy and Government Relations at Save the Children Canada.

Cicely sites self-harm, suicide, physical side effects of stress (such as developing diabetes) and/or developing drug and alcohol addiction (as a coping mechanism) as some of the risks faced by those suffering from toxic stress. “These are things that are equally life ending as a bomb dropping.” Says McWilliam.

“As a public or as a government particularly welcoming of refugees from conflict areas, we need to provide the supports [in and out of] schools to people experiencing toxic stress or PTSD more broadly.”

The extent of those affected post-arrival in Canada is currently undetermined, but the question remains: how prepared are Canadian mental health services to aid those who might suffer from the effects of toxic stress and PTSD?

The Canadian Centre for Victims of Torture has seen 588 families seeking treatment for help with PTSD and toxic stress. Muguleta Abai, Executive Director of the CCVT, explains that the process of treating children and families experiencing complications related to PTSD and Toxic Stress is long:

“It starts with the parents, the children or youths don’t come seeking treatment. The first step for us is to establish a rapport with the parents… and provide the support that they need, once they are satisfied with the rapport, that’s when the kids and the youths come.”

One issue organizations like CCVT are facing is the cultural differences related to counselling; “The other step is to organize family therapy sessions just to talk to the families in a welcoming environment, because the western style of counselling might be new for those people.”

The time it takes to treat an individual varies; “We don’t have one solution that fits everybody, there are some people who recover very quickly because they have their protective factors intact and there are others who don’t have their protective factors.”

Examples of protective factors are an intact family, having support in Canada, speaking the language of the host culture, and employment. “All of those things have a significant impact on their traumatic experiences because they can’t compound the problems that they face.”

There are also significant complications that can prevent refugees from getting the help they need in the first place. “One is lack of information, [second is] language, third is transportation (to see people that provide support) the major one is also the stigma attached to [problems with] mental health.” Explains Abai. “Among the Syrian refuges [the stigma] is even more [pronounced] than for Canadians.”

This point was emphasized by Yasser Aboutaha, of the DAR Foundation:

“Especially in our culture, for us a mental thing is so private, [they wouldn’t want] anybody to know about it except for professionals or close family members who can help.”

Mental health resources are challenged in their outreach to refugees because stigmatization is so strong and depends so heavily on clients to reach the decision on their own to get counselling in the first place and then to actively seek it.

“They wouldn’t be asking us [where to go] unless they know we can help them.” Says Aboutaha.

Another problem is the lack of affordable and appropriate specialists for refugees – the healthcare granted to a refugee in Ontario is equivalent to OHIP. While OHIP may cover the cost of a visit to a doctor or a psychiatrist, it does not cover a visit to a psychologist. In cases of severe trauma, victims “need somebody that they can talk with, a professional who is trained in the area of their trauma.” Says Stephen Conroy, a youth social worker at Sojourn House.

“My personal opinion is that what our clients could benefit from is to be able to access a psychologist.”

To effectively treat cases of PTSD or toxic stress, regular (and reliable) visits to psychologists are necessary. Even though places like the Canadian Centre for the Victims of Torture have services available free of charge, there are not enough resources to go around- they have only one Arabic-speaking counsellor, and 588 families coming to them for aid.

The stigma attached to seeking mental health aid coupled with the lack of affordable, regular and appropriate care are barriers that may prevent refugee children and youths from getting the help they need- help that could keep them from having severe health consequences in the future.

Click HERE to follow the journey a child takes from refugee camp to a new home in Oakville.

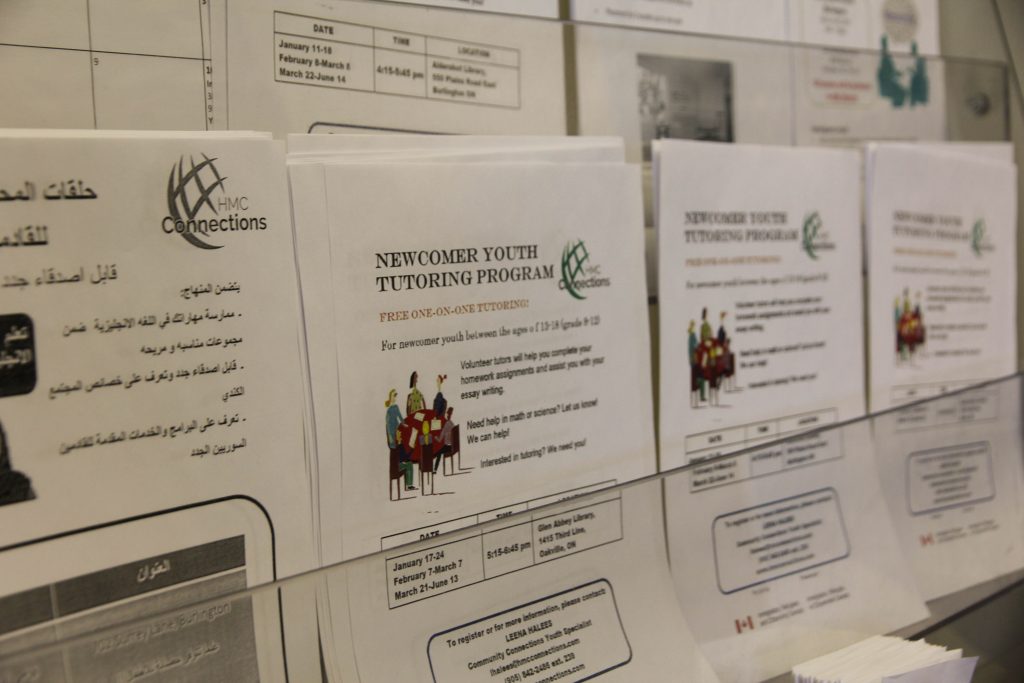

Click through the photo gallery below to view some of the programs in Halton aimed at meeting the needs of Syrian refugees:

Leave a Reply