The defeat of the Dutch anti-immigration Freedom Party led by Geert Wilders, who has been dubbed the Dutch Donald Trump, is be being celebrated as the victory of rationalism over nationalism.

But, even though Wilder’s officially lost, the adoption of some of his right-wing nationalistic ideology by the other Dutch parties means that Wilder’s ideas have won.

“Extreme populist politics is gaining power and I think its destructive for the entire world,” said Ozgun Alan, a Turkish computer programmer who has lived in the Netherlands for the past eight years.

However Dr. Edward Koning, a University of Guelph professor whose research focuses on immigration politics in Western Europe and North America, says that the Canadian takeaway from the elections is that the increase in extreme populist politicians is dangerous, regardless of whether or not they win or lose.

“The rise of Wilders has led a lot of politicians from other parties to adopt more restrictive positions on immigration as well because, they reasoned if we don’t do this, then these politicians will win even more. As a result, you are pushing your whole political spectrum in an anti-immigration, restrictive direction,” said Koning.

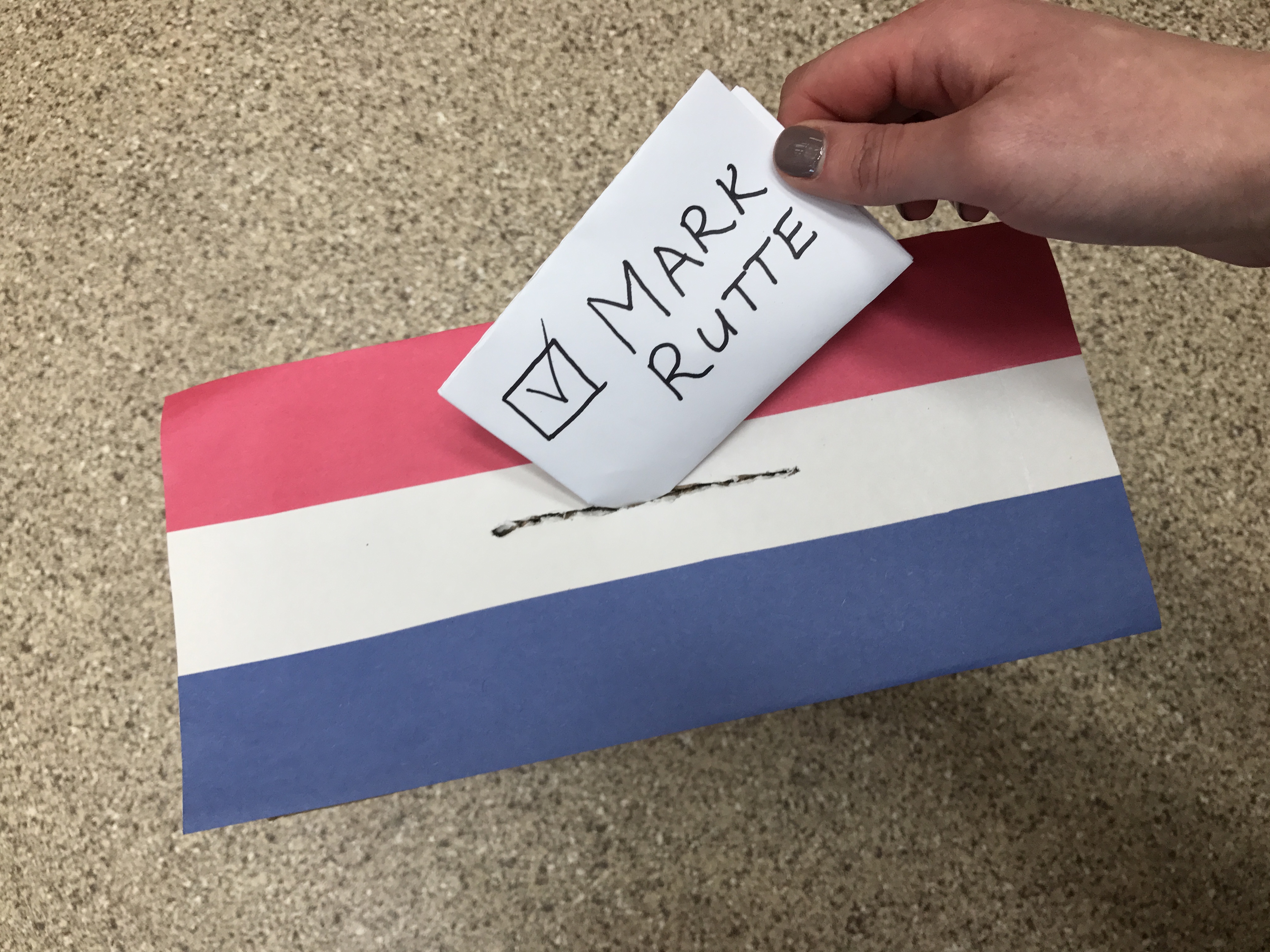

This push to a more restrictive anti-immigration stance has been viewed as one of the key factors in the success of the election’s winner Mark Rutte of the centre-right VVD Party.

“The VVD…to my surprise has been very strict on emphasizing that Muslims are a problem,” said Pim Veldhuisen, a 22-year-old university student in Delft, Netherlands, who voted in the elections.

“The middle parties adopted more [of a] drastic tone. So they adopted some of the populism in a mild form,” said Veldhuisen.

Old sentiment, new situation

The Wilders phenomenon is not a new development in the Netherlands. Both Koning and Veldhuiesen emphasize that Wilders has been a figure on the political scene for years. So too has anti-immigration sentiment.

What is more recent is the refugee crises which caused a spike in migrants and refugees seeking asylum in the Netherlands.

Koning said that Canada does not have the same degree of anti-immigration sentiment because it has a lower percentage of refugees entering the country. But, he warns that if there is an increase in refugees, then popular opinion in Canada will mirror that of Holland’s.

Not as tolerant as we think

Canada has been applauded on the international stage for its welcoming immigration and refugee policies. Last year, almost 40 thousand Syrian refugees were accepted into the country under Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s Liberal Government.

Yet, a McGill University study released last month shows that Canadians only marginally outrank the United States and Britain in terms of tolerance towards immigrants. The study’s author concludes that “there is potential for intolerant, anti-immigrant, and anti-refugee sentiment.”

Also, according to the National Council of Canadian Muslims, who track Islamophobic attacks, the number of attacks in 2017 is already double the number of those that took place by this time las year.

Federal conservative party leadership hopeful Kellie Leitch’s decline in the polls could be seen as an example of Canadians resisting her anti-immigrant platform. The success of her opponent Kevin O’Leary, whose immigration policies are inclusive of newcomers, reaffirms this view. However, earlier this month, O’Leary used his twitter account to condemn Canada’s Safe Third Party Agreement, a policy that enables people to claim refugee status after upon entry. He tweeted that it was a loophole in Canadian policy that is being exploited by asylum seekers illegally crossing the U.S.-Canada border.

This stricter stance towards refugees is more in line with the views of Leitch and other right-wing politicians.

It’s not over yet

The elections in the Netherlands may be over but the populist movement definitely is not.

Rutte’s government is strengthening its platform on immigration, with an increasingly tense diplomatic situation heating up with Turkey.

The night before the election, two Turkish diplomates attending a rally concerning Turkey’s upcoming referendum were denied entry into the Netherlands by the Dutch government. This action instigated a government standoff between Rutte and Turkey’s authoritarian leader Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

“The timing created a perfect storm,” said Koning.

Critics are arguing that the leader used this opportunity as a publicity stunt in order to gain voters.

“I am very curious how this really happened and to what extent it was planned out and how much it was influenced by the elections,” said Veldhuisen.

Koning is concerned about the backlash of this situation for both the Turkish and Muslim communities in the Netherlands. He said that “people who are prejudiced don’t really make all that many distinctions between Turkish and other people who they perceive might look like Turks, so those people who might have nothing to do with it might also feel the consequences of this. So, it’s definitely a very tense and volatile situation.”

Alan feels the situation was already problematic for Turkish people before the incident.

“Being Turkish in Europe is difficult because you face many prejudices or misinformation or ignorance,” said Alan.

He said that since he does not look like a “stereotypical Turk” he does not experience the same problems that some of his darker-featured Turkish friends have experienced in Holland. But, he is worried about what will happen to him and other immigrants if the nationalistic trends of the Dutch elections continue.

Leave a Reply