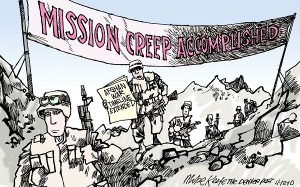

As the conflict in Mali devolves into erratic, guerilla style fighting, and Western military involvement drags on without any definitive end in sight, citizens on both sides of the Atlantic are becoming increasingly concerned with mission creep.

Far more perilous, however, is what actually makes mission creep possible: language creep, or the way we talk about terrorism. Since the birth of the War on Terror, the words we use to describe and contextualize terrorism have changed in subtle yet significant ways.

Language Creep

The evolution of our terrorism-related vocabulary, call it language creep, represents the real threat that opens the door to misguided military operations in the name of security, democracy and freedom.

Language, in its simplest form, is a symbol, and symbols can be loaded with implicit meaning. The term ‘Al Qaeda’, for example, has grown to be a symbol for everything that the Western world has come to associate with evil, death and destruction.

Al Qaeda “connections”

So when anything is labeled as having a connection to Al Qaeda, it automatically becomes threatening, and warrants some kind of armed response.

That’s why earlier in the year when British Prime Minister David Cameron, for instance, pontificated about the need for an increasingly muscular military response to the situation in Mali, he framed it as a defensive measure in the global battle against Al Qaeda.

And politicians like Prime Minister Cameron have been rather successful in getting what they want. The last 10 years demonstrate how easy is it is for a nation (or group of nations) to invade, bomb, or attack another country, as long as the attacking nation/s attribute their aggression to an act of self-defense against Al Qaeda.

It was easy at first. In the War on Terror’s post-911 glory days of Osama-hunting in the Tora Bora, an international coalition of countries tasked with dismantling Al Qaeda’s operational home base in the mountains of Afghanistan was an easy sell; Al Qaeda committed an atrocity, and it needed to be neutralized.

As the war shifted, however, so did the narrative when the Bush Administration famously linked Saddam Hussein’s Iraq to Al Qaeda. That connection was eventually exposed as being entirely untrue, but not before American and British forces found themselves in Iraq doing daily battle with Al Qaeda ‘affiliates’.

Al Qaeda “affiliates”

Affiliates is a highly ambiguous word in a global conflict context, but, clearly, it’s a useful one too; political leaders were able to use it to their advantage and achieve their goal- a war- by billing Saddam’s Iraq as an Al Qaeda hotbed.

Then as the US began its withdrawal from Iraq, ‘insurgencies’ emerged in other parts of the Middle East and Africa, and the language changed again. The new enemy was Al Qaeda ‘linked’ extremists in places like Somalia and Yemen.

Al Qaeda “links”

What it means to be “linked” to Al Qaeda is even more vague than what it is to be affiliated with it, but Western governments, their regional allies, and media outlets, for the most part, didn’t seem interested in shedding light on the distinction between the two.

Now, as violence ebbs and flows in Mali and threatens to spill into other parts of north and west Africa, the nomenclature du jour is Al Qaeda ‘inspired’ fighters; anyone who is “inspired” by Al Qaeda is the enemy.

The Al Qaeda trump card

This evolution of descriptors may seem innocuous, but what it really exploits is the ‘Al Qaeda’ trump card. This trump card exists as an opportunity for governments to bring conflict to the world’s most dysfunctional places under the guise of ‘defending against terror’, while simultaneously releasing themselves of any responsibility to consider the unique complexities of the historical, political and economic landscapes of these places.

That’s why the French can congratulate themselves for liberating northern Mali of Al Qaeda ‘linked’ Islamist fighters, and do not have to consider the role that violence and instability between the Tuaregs and neighboring ethnic groups (which predates 19th century French colonization) might play in the conflict.

That’s why the Americans can build a drone base in Niger to potentially kill Al Qaeda ‘affiliated’ members of Boko Haram in Nigeria, and not have to explain whether or not substantial Western investment in Africa’s fastest-growing economy plays a role in protecting the corrupt Christian governing party in Abuja.

Al Qaeda might still be a relevant player on the global stage- it’s nearly impossible to say, really. Considering the blood and treasure spent over the past decade ostensibly fighting it, however, governments, security officials and policymakers should at least have the decency to stop sloppily attaching ‘Al Qaeda’ to every local, national, and regional conflict in the Muslim world. It dishonors the victims, uniformed and not, who have died in this supposed War on Terror.